Poster presentation at the NorthTick conference

Abstract

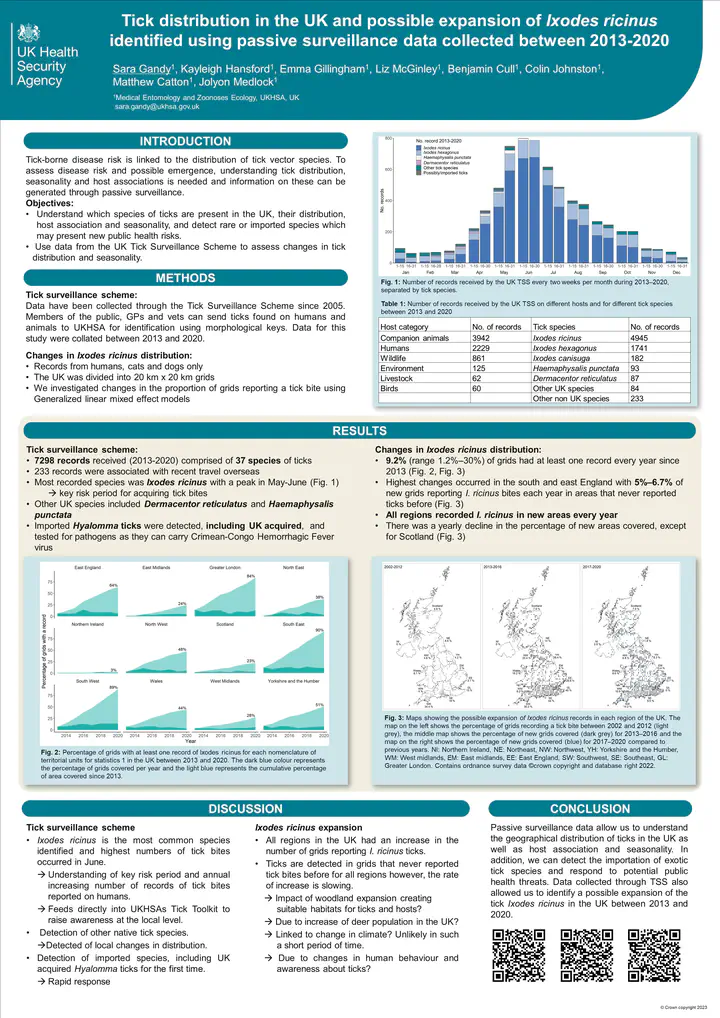

Tick-borne disease risk is linked to the distribution of tick vector species. Thus, to assess disease risk and possible emergence, understanding tick distribution, seasonality and host associations is needed and this can be achieved through passive surveillance. The aim of this study was to use data from the UK Tick Surveillance Scheme to assess changes in tick distribution and understand which species of ticks are present in the UK and their distribution. Data was collected through passive surveillance between 2013 and 2020. Members of the public, GPs, veterinary practices and wildlife charities were able to submit ticks found on humans and animals along with information about location, date the ticks were found and the hosts they were found on. We also investigated potential changes in the distribution of I. ricinus, the main vector of several pathogens including Borrelia burgdorferi s.l. (agent of Lyme borreliosis) and tick-borne encephalitis virus. We selected records of I. ricinus bites on humans, dogs and cats in the UK and we divided the UK into 20 km x 20 km grids. We then investigated changes in the proportion of grids reporting a tick bite for each region using statistical models. Between 2012 and 2020, 7662 records were received and 37 tick species were detected. Most records were acquired in the UK with only 237 that were associated with recent overseas travel. The dominant species was I. ricinus and records peaked during May and June, highlighting a key risk period for tick bites. Other key UK species were detected, including Dermacentor reticulatus and Haemaphysalis punctata as well as several rarer species that may present novel tick-borne disease risk to humans and other animals. Imported ticks were also detected, including Crimea Congo Haemorrhagic fever virus vector Hyalomma. When investigating potential expansion of I. ricinus, 9.2% (range 1.2%–30%) of grids had at least one record every year since 2013. Most regions reported a yearly increase in the percentage of grids reporting I. ricinus since 2013 and the highest changes occurred in the South and East England with 5%–6.7% of new grids reporting I. ricinus bites each year in areas that never reported ticks before. Spatiotemporal analyses suggested that, while all regions recorded I. ricinus in new areas every year, there was a yearly decline in the percentage of new areas covered, except for Scotland. To conclude, these data allowed us to better understand the tick species present in the UK and their distribution. In addition, we identified a possible expansion of I. ricinus between 2013 and 2020.